California schools will need to offer daily live interaction and regular communication with parents, among other requirements, in order to receive state funding for the upcoming school year.

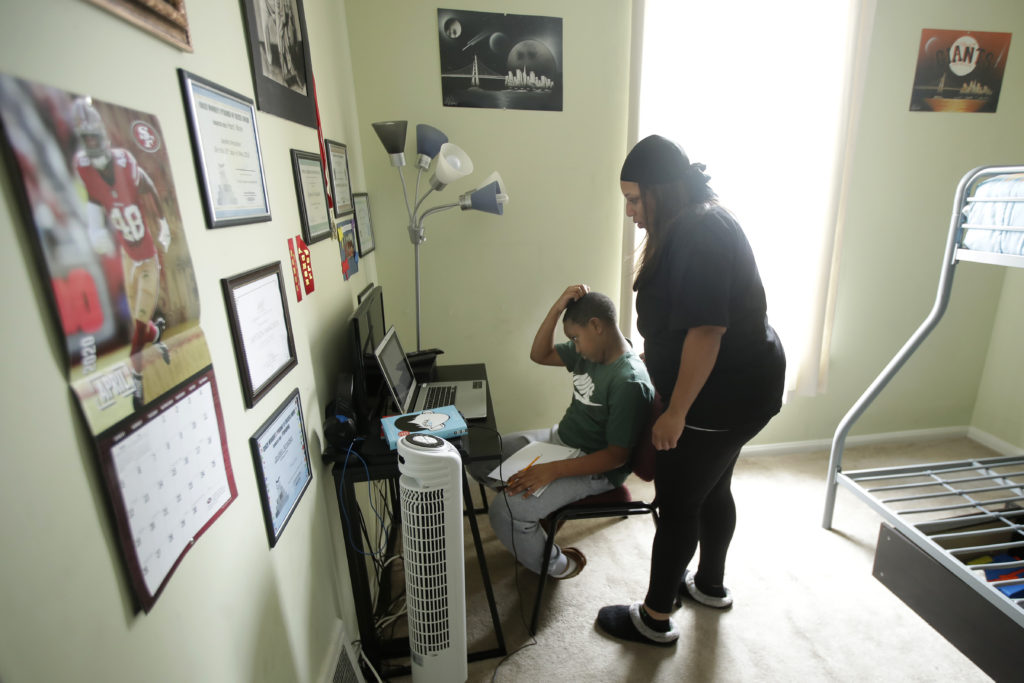

In March, schools across California closed their campuses to prevent the spread of Covid-19, causing districts to rush to put together distance learning plans, ranging from online group projects to virtual lectures to paper-pencil packets. With little warning, many teachers struggled to reach all of their students, raising concerns about how low-income students, English learners and other students with high needs are falling behind their peers with more resources at home to continue learning.

“Parents are so overwhelmed, many have said they don’t know how to do the work their kids are doing,” said Mary Lee, a parent advocate in south Los Angeles. “At some point, kids drop off. We have to have an overall consistent framework that requires administrators and teachers to put more emphasis on reaching out and supporting families.”

This fall, schools are being told to “offer in-person instruction to the greatest extent possible” according to AB-77, the education trailer bill accompanying the 2020-21 budget that legislators and Gov. Gavin Newsom agreed to this week. Schools can offer distance learning if ordered by a state or local health official, or for students who are medically at-risk or are self-quarantining because of exposure to Covid-19, which has killed more than 5,630 people in California as of June 23, according to the California Department of Public Health.

But some education groups say the latest provisions are restrictive and safely reopening schools will be nearly impossible to implement without extra financial support. A group of civil rights and education advocates on Thursday released a floor alert calling on lawmakers to strengthen the provisions even further before voting on the bill this Friday.

Specifically, the group is asking for a baseline requirement of at least 3 hours a day of live face-to-face instruction in-person or online, along with a mechanism to identify and “correct egregious LEA underperformance in distance learning,” the letter reads. They also are calling for clear avenues for parents and students to seek help if they are receiving a subpar education, and for lawmakers to close a loophole in the trailer bill that could allow districts to divert funding targeted towards low-income students, English learners and Black and Latino students.

On June 8, California released updated guidelines for reopening schools that recommend limiting the number of students physically on campus at the same time and considering strategies such as hybrid learning models where students participate in a mix of in-person and online classes. So far, it appears many districts in California are headed towards a hybrid model.

The latest distance learning rules in AB-77 also require teachers to confirm that students have the necessary technology at home to participate in distance learning. Access to computers and the internet has been a major impediment to connecting students with teachers during school closures.

California still needs more than 700,000 laptops and more than 300,000 hotspots to meet students’ needs moving forward, according to recent estimates from the California Department of Education.

Teachers participating in distance learning will also be expected to interact with students live daily to teach, monitor progress and maintain personal connections. Interaction can be over the internet or telephone, or through other means approved by health officials.

The bill also instructs teachers to communicate with parents about student learning progress.

One distance learning success story that researchers and education leaders have pointed to is Miami-Dade County Public Schools in Florida. The district was able to kick-start distance learning immediately after schools closed in March after distributing more than 100,000 laptops and Wi-Fi-enabled phones to students. It also had a plan for tracking attendance and established clear class time expectations at the start, including daily 45-60 minute lessons and live office hours with teachers.

After reaching out to families of students who didn’t initially log in, the district of more than 300,000 students reported a 99% participation rate.

In California, advocates for more guidance stress that students benefited from more face-to-face instruction during distance learning, especially among English learners. However, 40% of teachers said they offered only 0-1 hour of live instruction each week this spring, according to a survey of more than 650 California teachers and administrators by Californians Together, a research and advocacy group focused on English learners.

“My ability as a mother is different from a teacher, so it was difficult to become her teacher so suddenly,” said Gipsy Alvarado, an east Los Angeles parent with a daughter in kindergarten. “You have to make sure you are next to them. In school, they are next to their peers and teachers. Academically it’s been a total loss. She was used to extracurricular activities, and now we don’t have that routine.”

Education advocacy groups that pushed for more specific guidance found some relief in the guidelines, saying they provide necessary standards to ensure that more students progress in their learning.

“Our huge concern here is that too many kids have been getting very little instruction. That tends to fall disproportionately on kids of color, English learners and kids in poverty,” said Ted Lempert, president of Children Now, a non-partisan research and advocacy organization focused on children’s health and education in California. “In some cases, kids aren’t getting anything.”

Children Now is part of a group of education and civil rights organizations that earlier this month wrote a letter calling on lawmakers to maintain requirements for instructional days, attendance and set higher standards for reaching children during distance learning.

But education groups differ on what seems feasible for schools, many of which are facing drastic budget cuts and other financial concerns resulting from the pandemic.

“The push toward on-campus instruction, while understandable, doesn’t make sense in a health context when legislators have to know that many districts do not have the funding, the facility space, or the capacity to safely offer on-campus instruction en masse at this time,” said Troy Flint, spokesman for the California School Boards Association. “It appears to undermine the priority the governor has placed on health and safety.”

The California School Boards Association was a part of a group that also wrote a letter to state legislators after the May budget proposal asking for more flexibility with instructional time requirements, as well as additional funding in order to reopen schools safely.

“It might be different if we saw additional funding above the norm to recognize what is required to address this crisis, but that does not appear to be forthcoming,” Flint said. “Essentially this trailer bill sets schools up for failure.”

California teachers and school officials preparing plans for distance learning in the fall got a reprieve this week in the latest state budget, which will avoid previous plans to cut K-12 funding by nearly $7 billion.

To address learning loss during school closures and ease re-opening costs, Newsom also agreed to add $1 billion in one-time funding from the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act and to distribute the money to districts. The total CARES Act funding for K-12 will rise from $6 billion to $7 billion.

But safety protocols (such as sanitizing surfaces) and purchasing technology equipment for students will be expensive for many resource-strapped districts.

Even with the additional CARES Act funding, Flint said, “that would mitigate the crisis but it would not solve the problem at all.”

California schools will continue to be required to provide 180 days of instruction per year (175 days for charter schools). However, the minimum number of instructional minutes will be reduced, in an effort to offer teachers more flexibility during distance learning.

The typical minimum number of instructional minutes per day varies by grade: 200 for kindergarten, 280 for grades 1 to 3; 300 for grades 4 to 8 and 360 for high school. For the 2020-21 school year, the daily requirements will drop to 180 minutes for kindergarten, 230 for grades 1 to 3 and 240 for grades 4 to 12.

California bases funding to schools on average daily attendance, but districts won’t lose money if some students don’t participate in distance learning. However, schools will still be required to track and report student participation.

“Providing flexibility to school districts on average daily attendance and instructional minute requirements will help address equity needs and accommodate distance learning as needed to serve all students,” said California Teachers Association President E. Toby Boyd. “Still, a lot of work remains to safely reopen schools and colleges. Whether it is enhancing ventilation systems, accommodating for social distancing, providing face coverings and cleaning supplies, or having the necessary staff for health screenings and emotional support, schools are going to need additional resources.”

Additional requirements for distance learning outlined in the trailer bill include setting procedures for re-engaging students who are absent for more than 60% of instruction per week and providing academic supports for English learners and students who have fallen behind in their academic progress. Progress can be assessed through a variety of ways including evidence of online activities, assignment completion and contact between school staff and students or their parents.