A lright — you’ve got it. The screenplay idea that will change the world, break box office records, and win you every single Oscar. Only… you don’t quite understand how to format a screenplay. Do you even really need screenplay format?

Our answer? A resounding “Yes!” Screenplay format is necessary if you want anyone to take your magnum opus seriously, but more importantly? It’s necessary if you want your script to become an actual finished film.

A movie script or screenplay is the blueprint for any feature film, TV show or video game. Scripts includes characters actions, dialogue and movement as well as stage direction. Movie script format has a unique set of industry standard rules, which are slightly different than the script writing format used in a shooting script. A shooting script is a more precisely formatted version of the script, used in Pre-Production and Production to turn the screenplay into a film. This version can include elements like camera directions, music cues or transitions.

It’s not just stylistic and the "rules" are not arbitrary. Industry standard script format has many functions and benefits through the filmmaking process. A draft in proper screenwriting format denotes professionalism, otherwise it appears amateurish and would likely get tossed before the end of page 1.

Proper film script format also plays a large part in the script breakdown process, one of the most important steps in turning a screenplay into an actual film. Film budget planning and crafting a shooting schedule are both informed by screenwriting format.

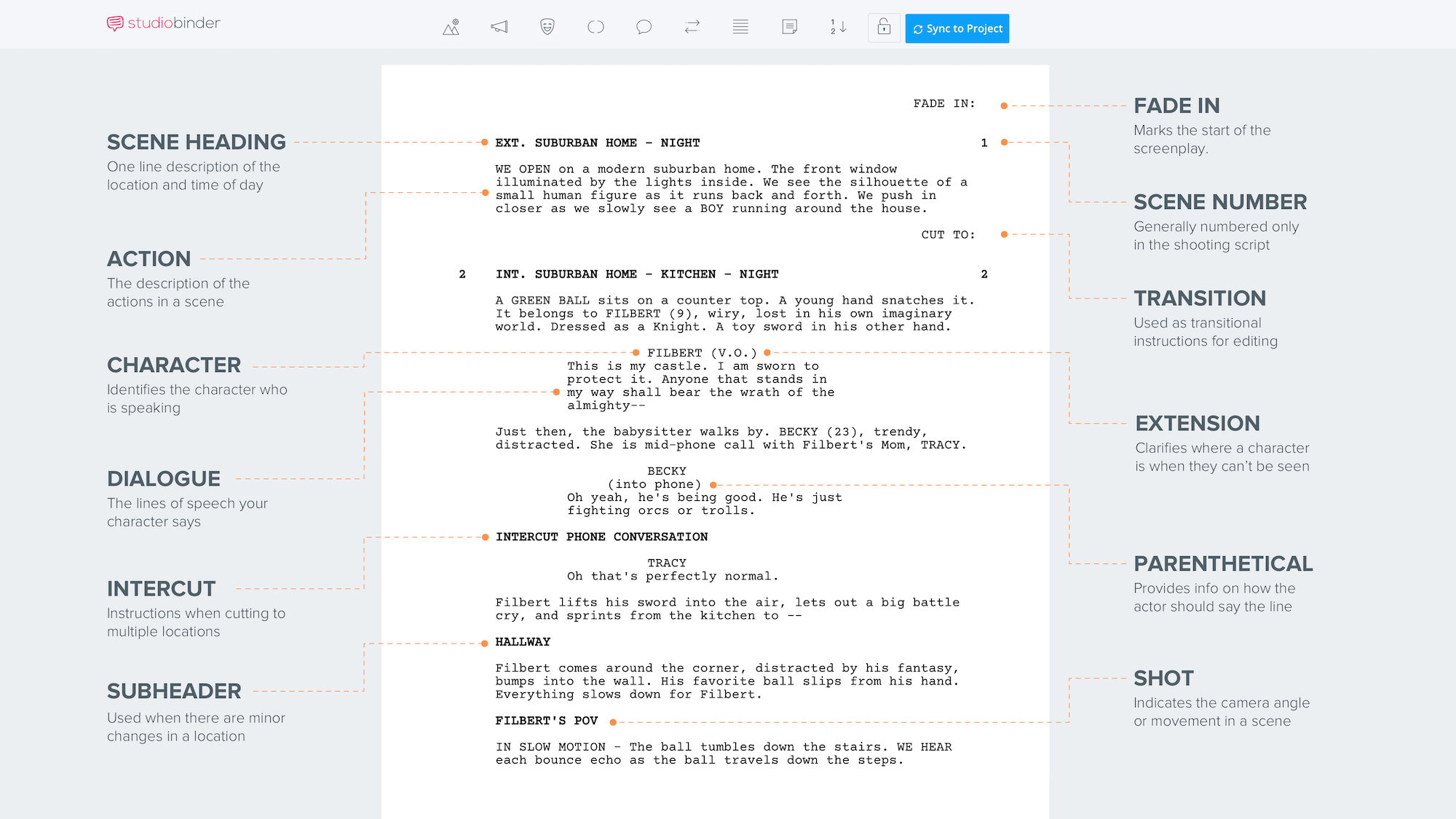

In this screenplay template, you can see all the major elements and their positioning on the page.

Rather than replicate these movie script format rules manually, most writers choose a dedicated script writing software like StudioBinder. This removes all the guesswork and lets the writer focus on what's most important — the story you're trying to tell.

Proper screenplay format will make this process immensely easier. Using these elements correctly is essential to proper script writing format. This is true for everything from short film scripts to million-dollar blockbusters.

For more research to see how professional screenwriters handle screenwriting format, you can read and download over 250+ screenplays in StudioBinder's script library. Now, let's get to specific elements found in screenwriting format.

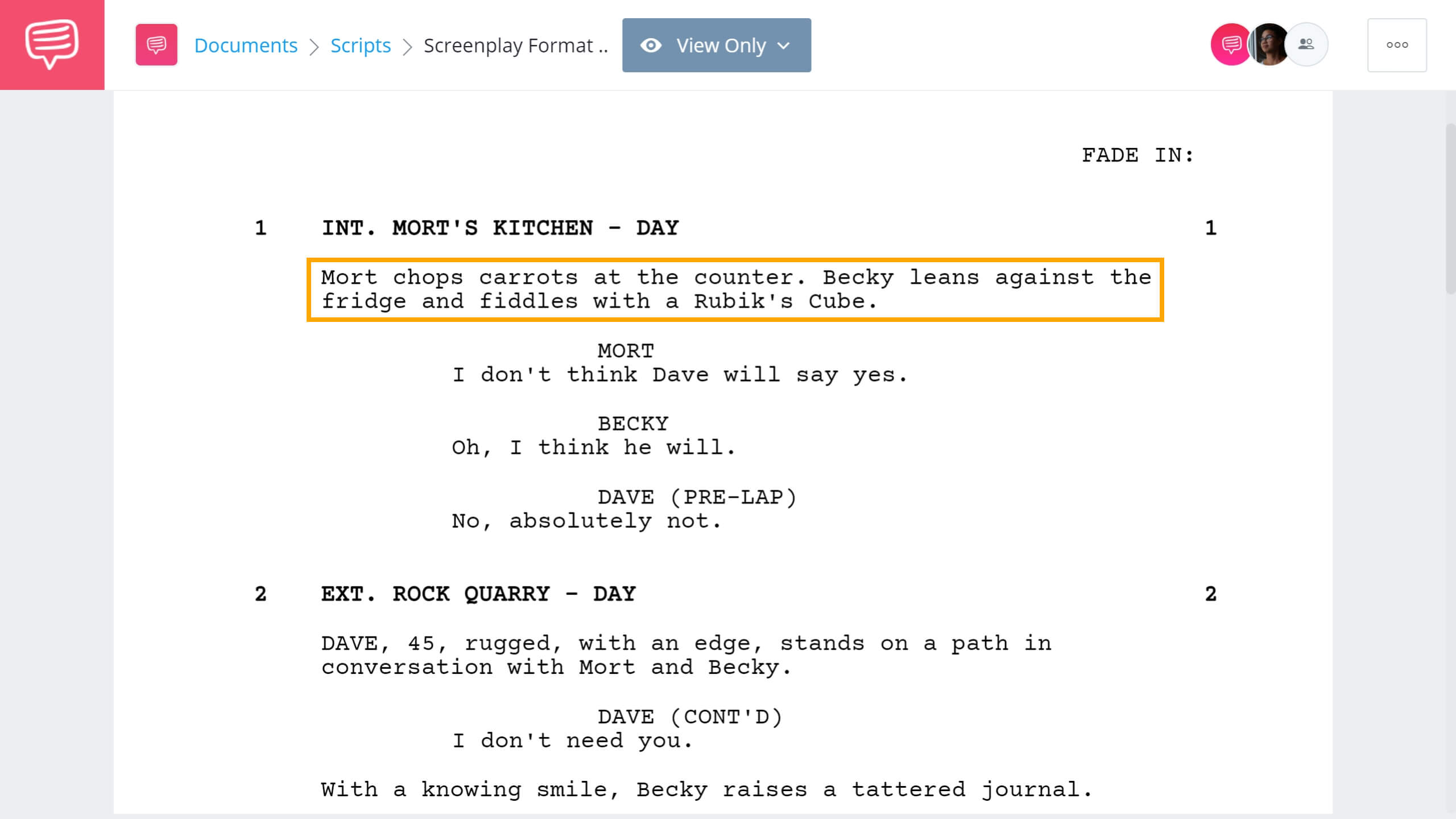

Sluglines (also known as scene headings) tell the reader where the action is happening. It’s a location, followed by a time, and looks something like this.

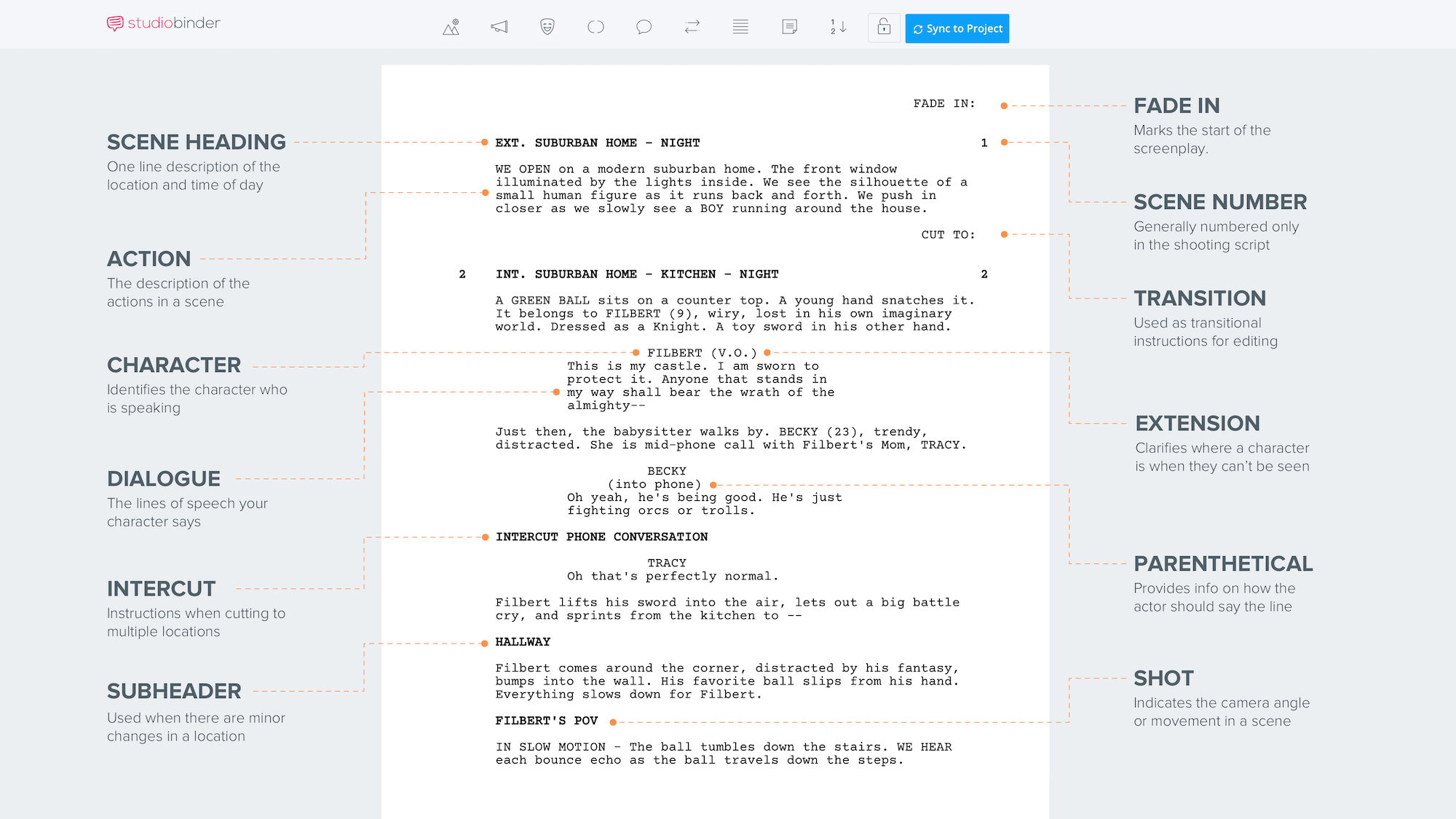

In this screenplay example, you'll see that Scene 1 starts in Mort's Kitchen but what does INT mean in a script? When it comes to sluglines, you first have to establish whether the scene takes place inside (INT.) or outside (EXT.)

Then add the location of the scene, followed by the time of day (Day, Night, Morning, Evening, etc.).

When a scene directly continues from the previous scene, mark it “continuous” in the time slot. If it's a couple minutes later, feel free to use "moments later" in your slugline.

Sometimes you’ll have a scene that takes place in both an interior and an exterior. Most of the time, this will be in a moving vehicle of some kind. In those cases, start your slugline with “INT./EXT.”

If you’re using screenwriting software, it will format it correctly for you, but if you’re doing it yourself, be sure to put the entire slugline in ALL CAPS.

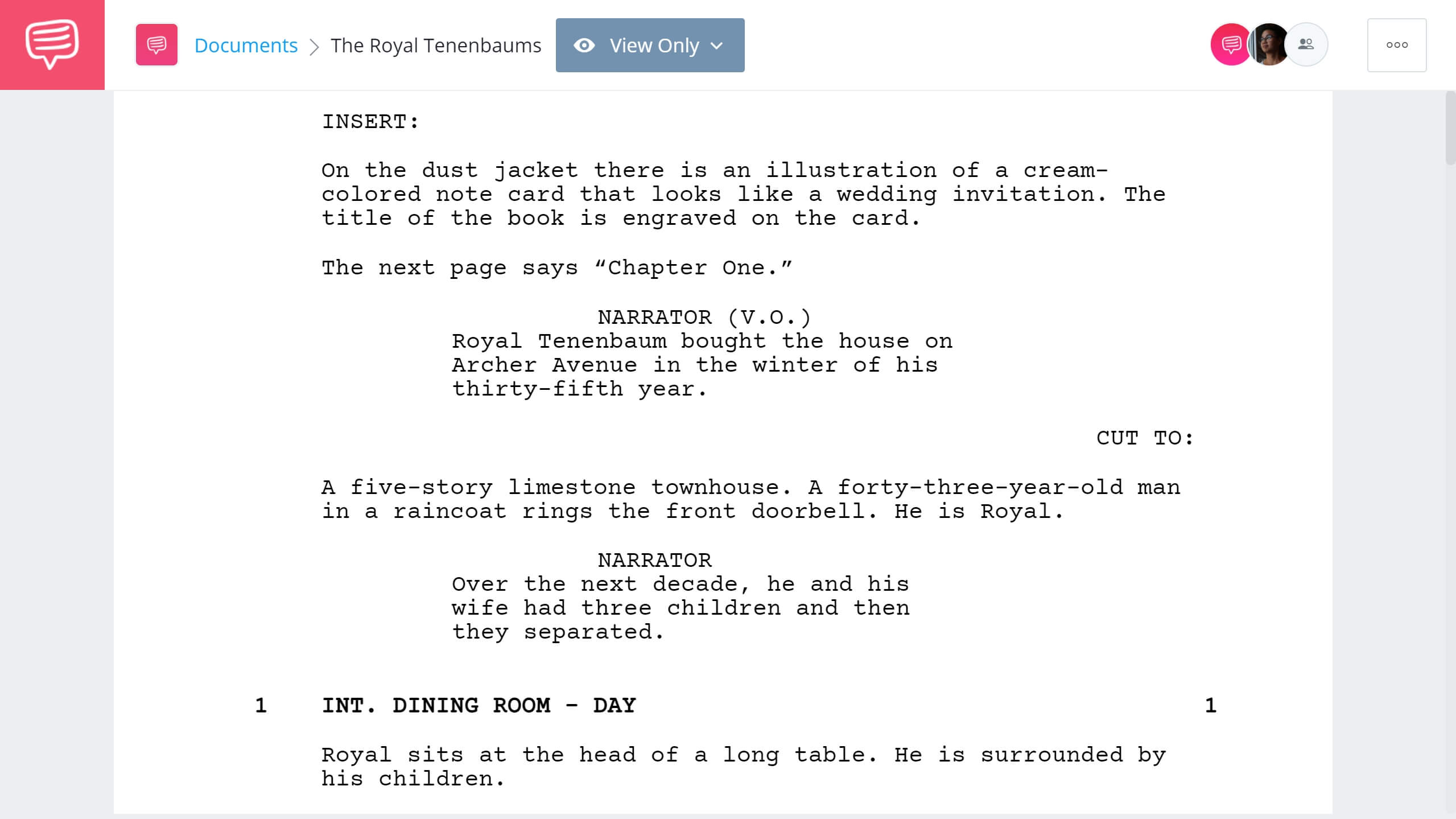

Click below to read the full screenplay for The Royal Tenenbaums where you can see how sluglines work in a script.

Sluglines are important because they are how your assistant directors and line producers will plan out how things get shot.

The difference between one scene being night and the next being day is important to continuity for hair, makeup, and wardrobe departments.

That's why this is one of the most essential elements in movie script format — it tells you when and where a scene is taking place in the grand scheme of the script. Knowing the time of day and where the scene takes place affects nearly every department in a major way.

Next up, we'll talk about how to write actions in a script.

Your action lines go right beneath the slugline. Proper screenplay format dictates that they always be written in the present tense and as visually descriptive as possible.

Here's a script format example of action lines in a screenplay. Note that the actions are written as "just the facts" in a clear and readable way.

Specifically, action lines tell the reader what they will see and hear in the finished film other than dialogue. And don't take the "action" part too literally — this element covers everything, including fight scenes. In this video, watch as we demonstrate how to write a fight scene like John Wick in 5 minutes.

When it comes to screenplay format, clarity is king — remember, a script is a document to be turned into a movie, not really read on its own.

Department heads will take things literally and, oftentimes, without question. So if you write something ridiculous in the description, they'll take it upon themselves to figure out how to make it real — that's their job.

Make sure you're deliberate and precise with your action lines. Find the balance between letting a director direct a scene, and giving the Propmaster enough information to get exactly what you want.

This is especially true if you're trying something as chaotic as writing a fight scene or writing a car chase, where every detail has to be planned out. The more complicated the production, the more important it is for you to follow proper script format. This type of work is why screenwriting format was developed the way it was.

There are two hard and fast rules for capitalization in screenplay format. Always capitalize a character's name the first time they appear in the action/description, and always capitalize screenplay transitions.

Beyond that, you can also capitalize important props, sound design, and camera movements.

Anything you want to use the movie script format to call out things important enough to merit the attention of those doing the script breakdown.

Just don't go overboard with it. There's nothing more annoying and CONFUSING then when someone RANDOMLY capitalizes EVERYTHING ON THE page.

After the action/description, when a character speaks, we start with their name. You center and capitalize a character ID and put dialogue underneath. Your character ID need not be your entire character’s name. It could be a first name, a last name, or an alias.

Whatever best identifies the character as that character. And stay consistent — if a character is identified as "McCloud," he stays McCloud, even if we eventually learn that his first name is "Jack."

The only exception to this rule is if your character goes in disguise, especially if they fake a voice whilst disguised.

For example, this person would be "Bruce Wayne."

While this person would be "Batman."

Even though they're technically the same person in a different costume.

If you find that to be too confusing, another method is to use a slash. "Bruce Wayne" becomes "Bruce Wayne/Batman" whenever he's Batman, and just regular Bruce when he's not.

Dialogue is straight-forward. At least in terms of formatting. Writing good dialogue is a topic all its own.

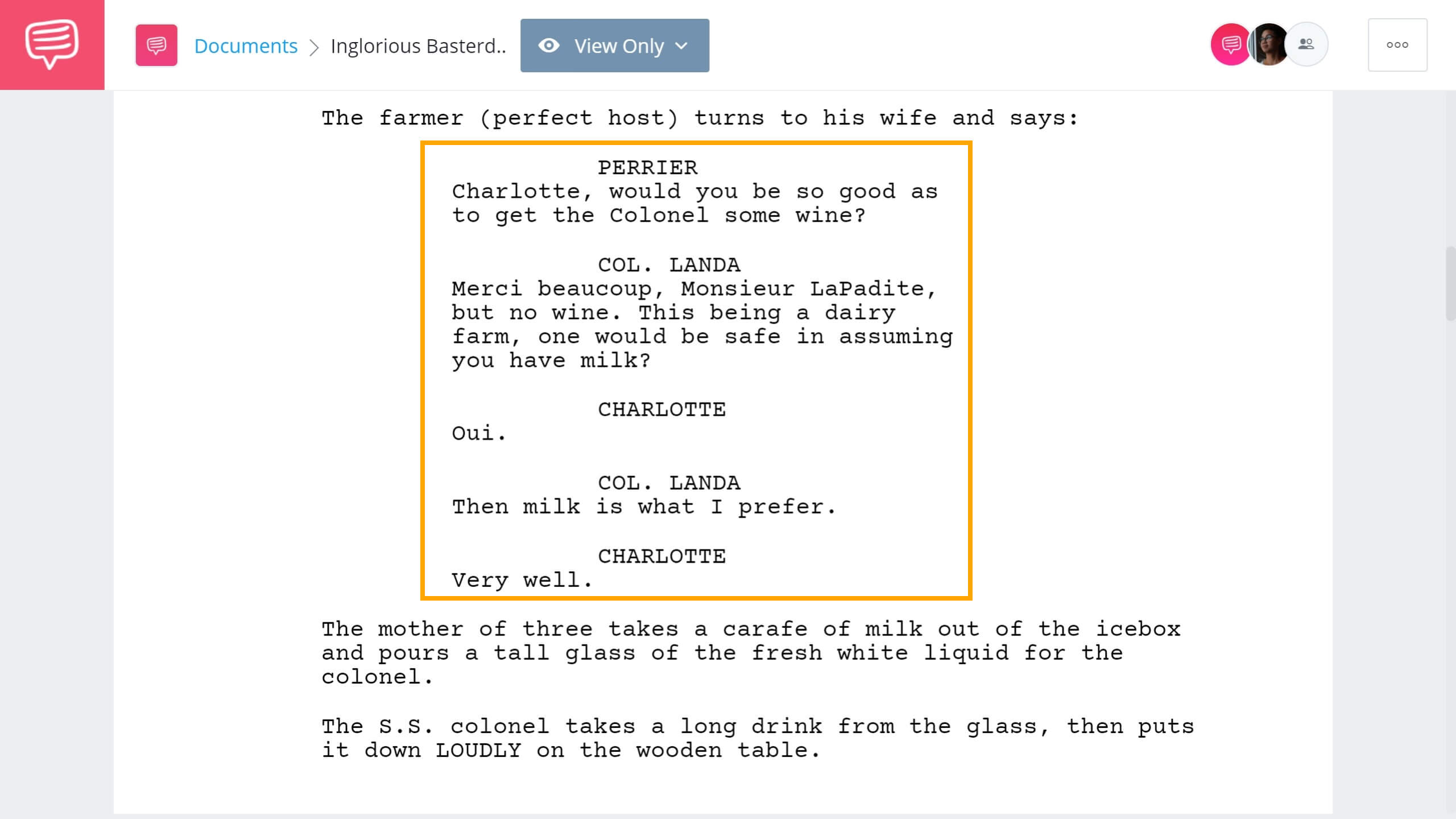

Here's how dialogue looks in actual screenplay format. The margins on either side of the dialogue keep it restricted to the middle of the page. This allows for extra white space on the page for notes.

Notice the sample screenplay below from Inglourious Basterds to see how to format dialogue in a script. Follow the image link to read the entire opening sequence, including the moments that never made it into the final film.

When writing dialogue, the idea is to let the characters speak for themselves. Always front and center, of course, is the reality that you, the writer, are shaping those characters.

Therefore, by using software that takes care of screenplay formatting automatically, you can give your attention to the characters and their lines.

Extensions go next to a character name in parentheses and tell us how the dialogue is heard by the audience. Most screenwriting software will provide the standard screenplay format extensions once you start typing the parenthetical.

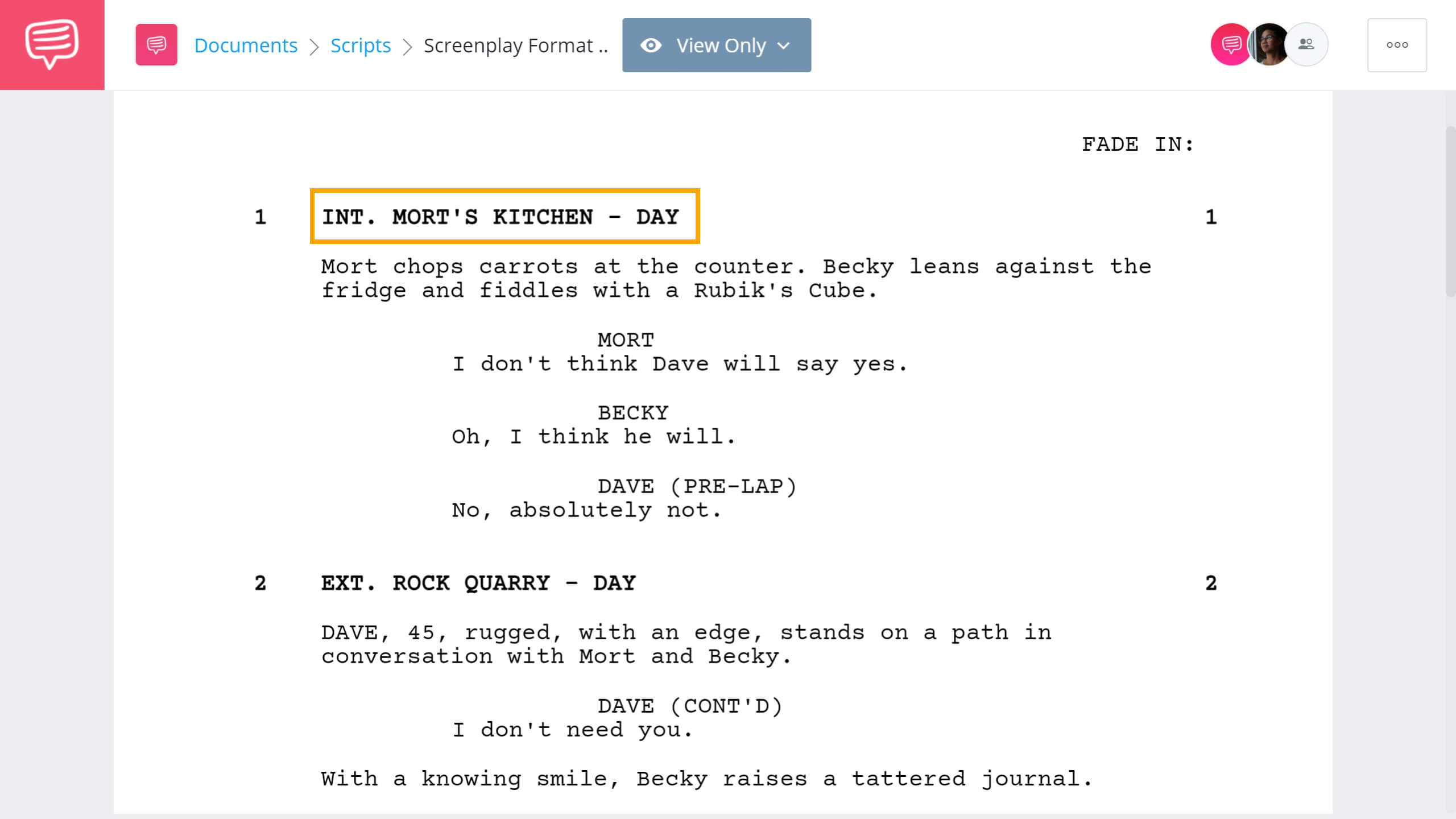

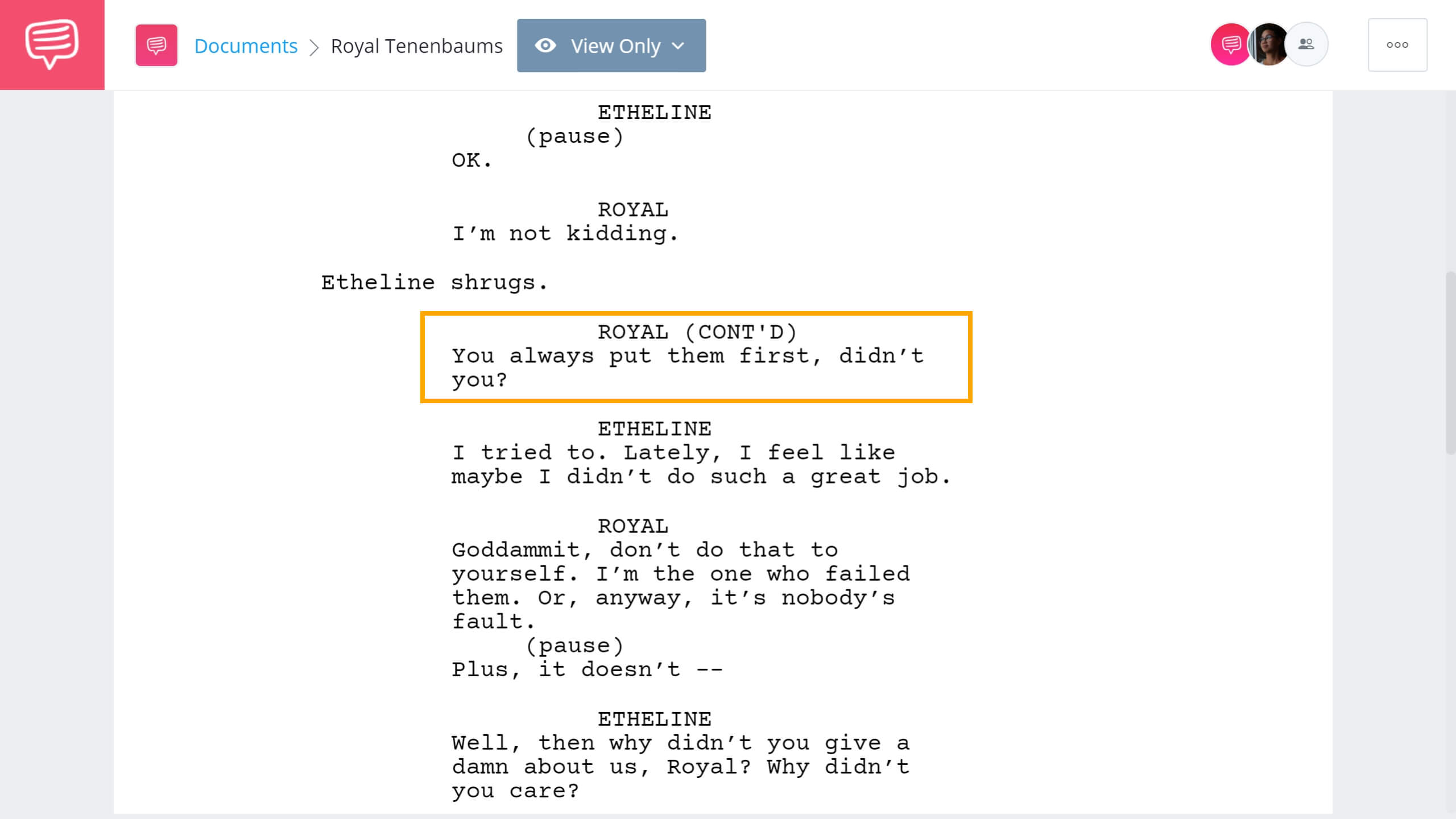

You'll also occasionally used (CONT'D) next to the character's name to indicate the continuation of their lines after they're "interrupted" by some action/description. Consider this moment from The Royal Tenenbaums, one of Wes Anderson's best movies. In this scene, Royal's dialogue is broken up by Etheline's action so we apply a (CONT'D) extension next to Royal's name.

Voice over is when a character is speaking over the action, but isn’t heard by the other characters in the scene. Usually narration, but can also be a character's internal dialogue. Learn more about how to write voice over in a montage using proper script writing format.

When a character is speaking and is heard by other characters, but can't be seen by the audience or other characters. Just write (O.S.) next to the character's name. "Off camera" written as (O.C.) is also acceptable.

Examples of extensions include:

Fairly self-explanatory — characters speaking into their phones or radios, rather than to each other in person.

This is most useful when characters are speaking to someone on the phone and someone right next to them. Or when using a local news station to lay out the story's exposition. Learn more with another script format example.

Pre lap is dialogue from the next scene that starts before the current scene has ended. Simply write "pre lap" in the parentheses next to the character's name.

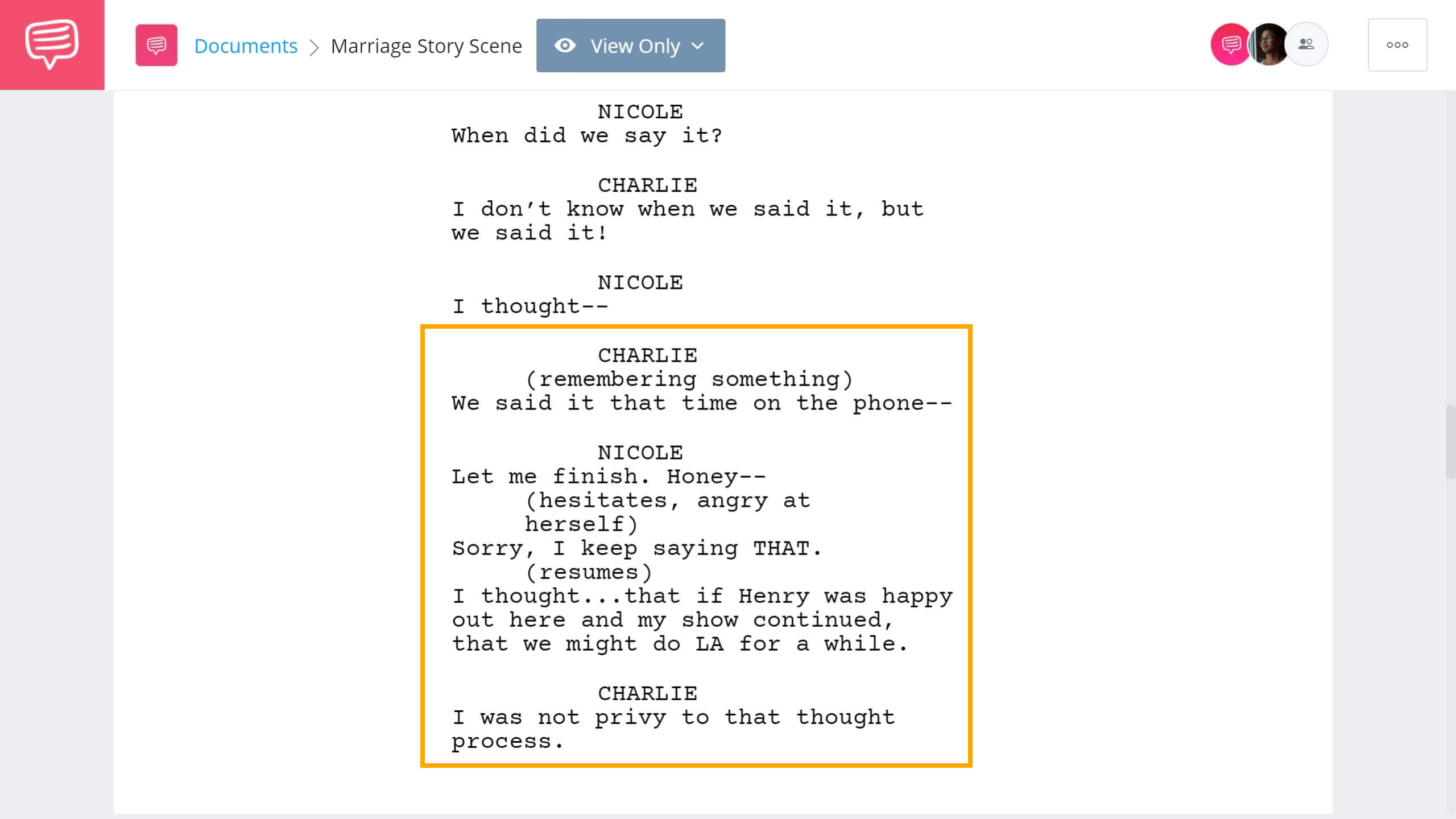

Parentheticals can seem like extensions at first glance, but there are a few key distinctions. Extensions are technical directions — they explain where the person saying the dialogue is in the scene.

Parentheticals are directions to the actor – they detail how the line should be performed.

Here's an example of a parenthetical in proper screenplay format. This is the absolutely crushing scene in Marriage Story. Notice how writer/director Noah Baumbach uses parentheticals to map out the internal conflict for his characters. Make sure you read the entire scene to see how Baumbach uses the combination of dialogue and parentheticals to craft a multi-layered and emotionally dynamic scene.

As far as script format goes, parentheticals are placed directly beneath the character ID in (parentheses). Some examples include:

If you're using screenwriting software, it's important to change elements when writing parentheticals. You can't just write them into parentheses and hope it reads correctly!

Screenplay transitions indicate how an editor should switch between two scenes — they're on the far right of the page (right justified) and placed between two scenes. Proper screenplay formatting usually indicates these as being capitalized.

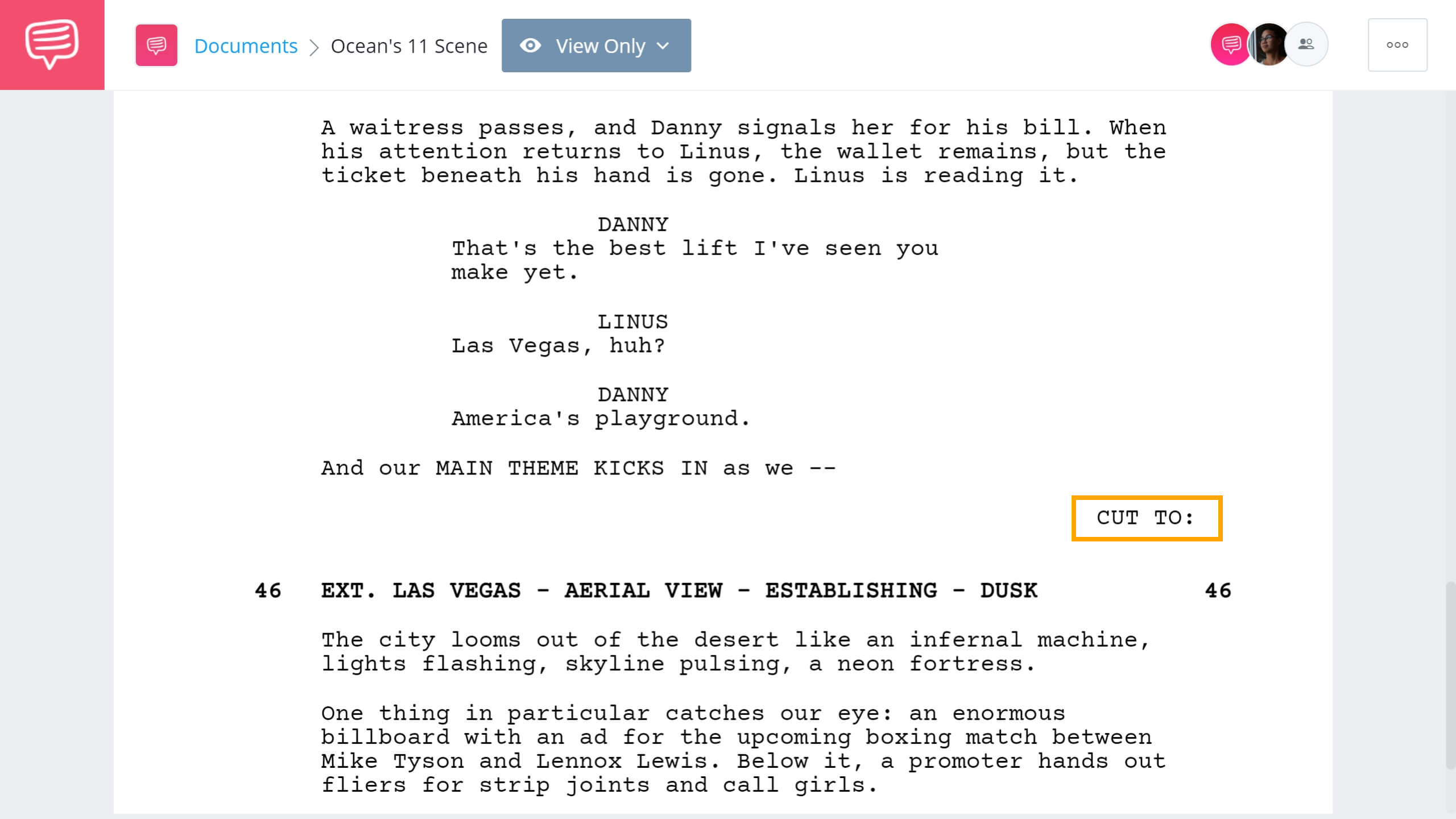

So, rather than mark everything with a “CUT TO:” only use screenplay transitions ONLY when you want it to stand out in some way. For example, in this moment from Ocean's Eleven, writer Ted Griffin uses this transition to emphasize the switch of location to Las Vegas.

Pay attention to how the dialogue and description build momentum going into the next scene, which is punctuated by the "CUT TO:" transition, and concluded with a vibrant description of Sin City.

Knowing how to use screenplay transitions is a major part in knowing how to format a screenplay. These days, however, most editors know that no transition indicates a standard cut.

The "CUT TO:" is also widely used when formatting multi-cam television scripts as it marks the end of a scene. Because multi-cam scripts are formatted with page breaks for both scenes and acts, it's important to mark the ending of the scene versus when it's an act break, which is also a commercial break.

Much like with parentheticals, your screenwriting software will likely have the other standard screenplay transitions preloaded for you. These include, but are not limited to:

This is a really abrupt cut, like a "CUT TO:" times ten. The kind of cut that comes in mid-sentence. Smash cuts are used here to as a form of montage (which we'll get into later).

When one scene “dissolves” into another scene, almost transforming into that scene. This is primarily used to indicate that time has passed.

A tricky form of edit — where you cut the film so the last shot in the previous scene (say, a hand reaching for a knife) matches the first shot in the new scene (a hand reaching for an apple). Here are some example of how and when match cuts are used in film to give you an idea of how they might be written.

Intercutting (or cross-cutting) is where you bounce back and forth between two different scenes. It’s usually used for phone calls, but not always.

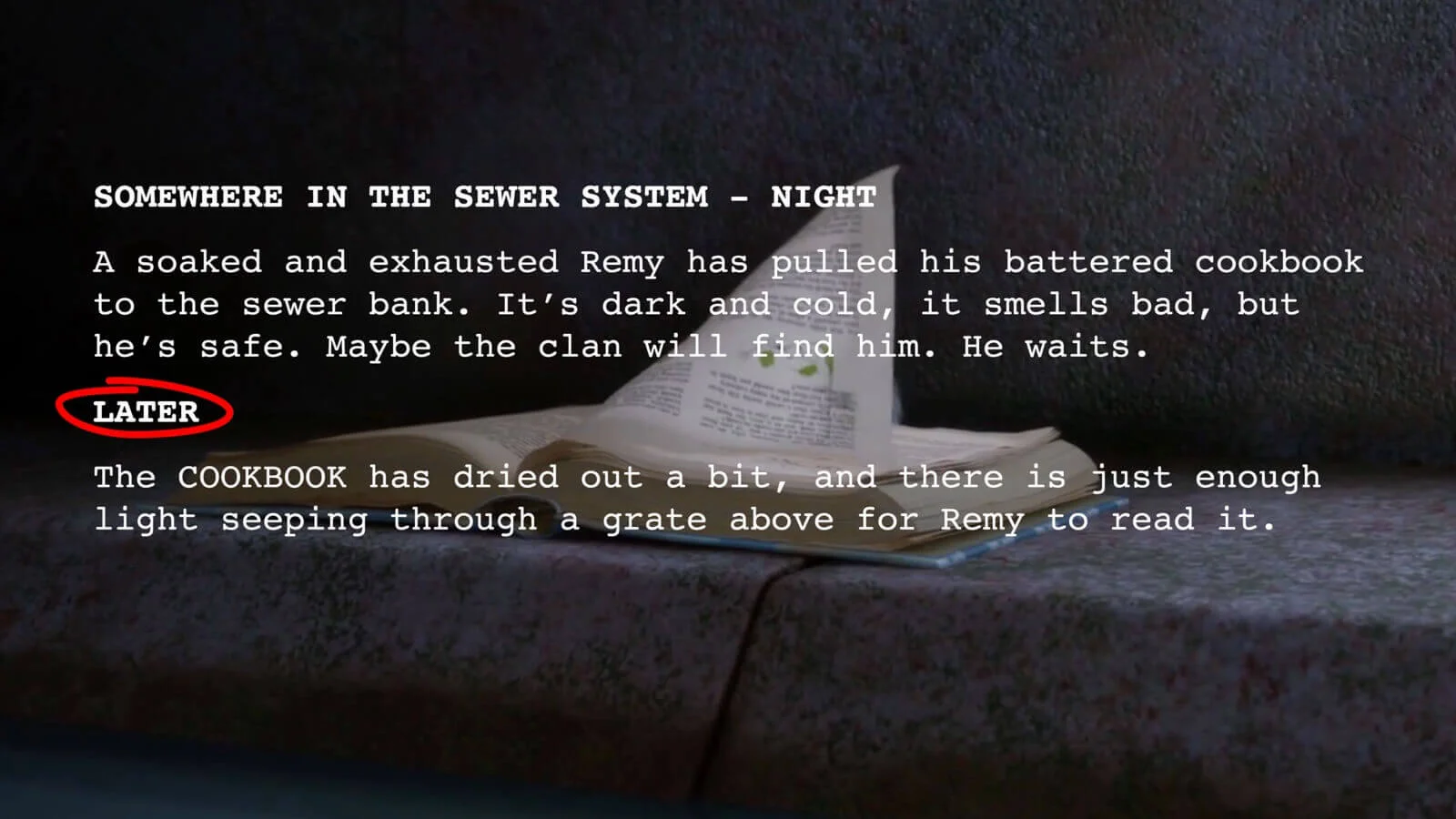

Subheaders are like mini-sluglines that indicate another place or time within a scene. They’re even formatted like sluglines — left-justified and capitalized. Take a look at this example to get an idea of what we mean:

If you’re using screenwriting software, you’ll probably have to format it as a “scene header” — that’s perfectly fine!

If you’re shooting within a large house, a subheader might be used to indicate a change in rooms. From the creepy FOYER to the haunted LIBRARY, for example. Or to indicate a detail of a certain location.

Or you might want to use a subheader to indicate a jump in time. If a cop is on a long stakeout and you want to show that time has passed, you’d throw it under the subheader LATER.

This is one of the gray areas in script format where some (mostly those in production) say it should be slugged as a new scene (since it's a different time and may require a different setup).

Writers, on the other hand, tend to prefer to save the line so they don't push a page. So instead of saying INT. CAR - LATER, which requires more space, they'd just say LATER and continue the scene since it never changed locations. Either way is proper script formatting, but using subheaders is more casual.

Formatted like a caps-locked action line, shots direct our attention to a specific visual or way of seeing something. This can include various camera shots, camera angles or camera movements.

In modern times, they're typically used by writer-directors, but also when the writer feels that a visual is key to the entire scene and wants to be sure the director knows it.

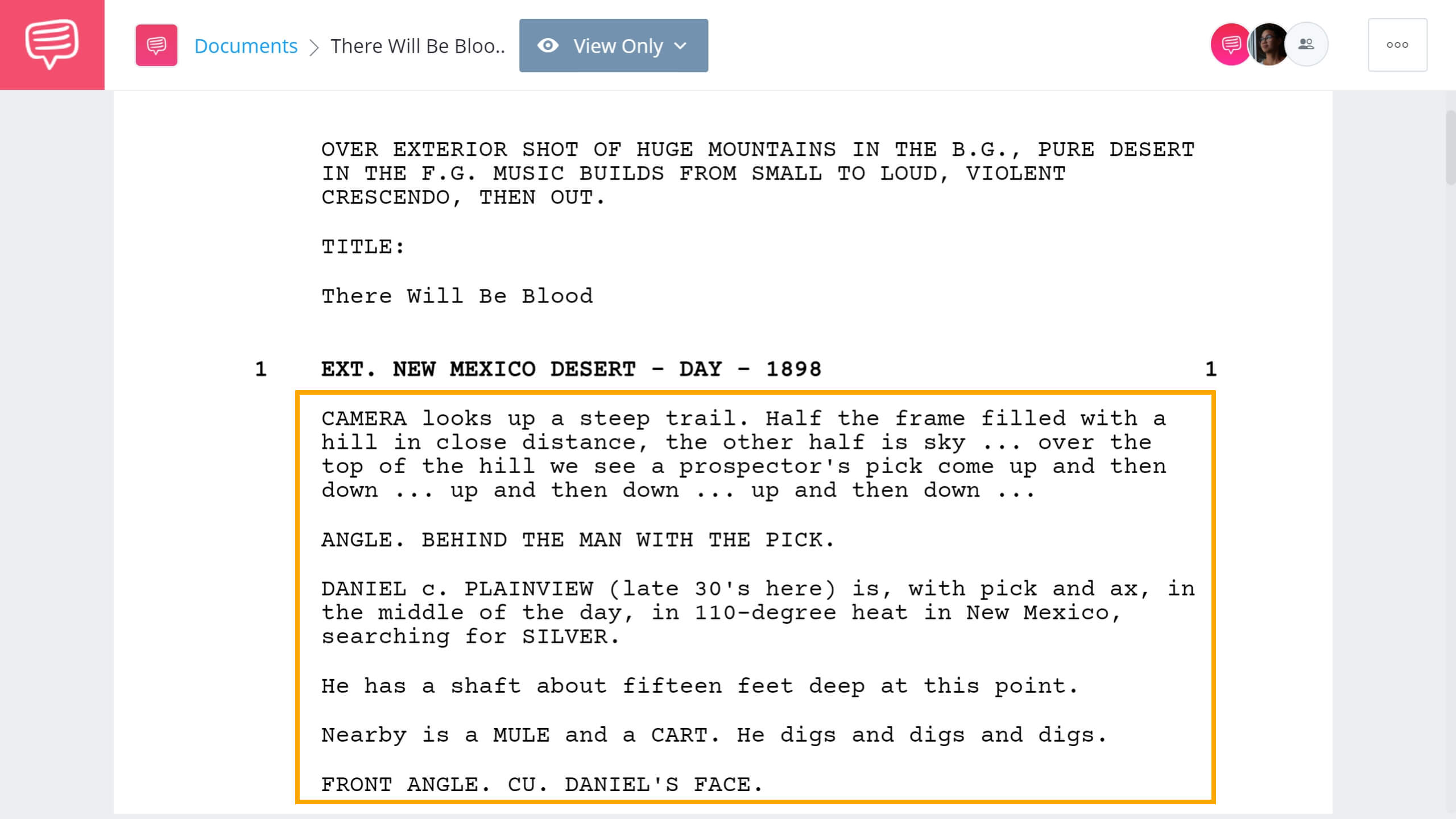

Here's a screenplay example from There Will Be Blood, where P.T. Anderson (who will also eventually direct the film) writes multiple shots and angles throughout. Again, unless you're directing the film, it's best to leave these decisions out of your script.

For this script example, we've included the entire opening sequence so you can see for yourself how Anderson tells us everything we need to know about this character without a word of dialogue.

Most screenwriters today only specify shots when it's absolutely critical to the interpretation of the scene.

By indicating various shot types in a script, keep in mind that you as a writer are also hammering home to the reader that this is a movie and cameras will be recording it. On a certain level, this can take the reader out of the story, so you might want to use the technique sparingly.

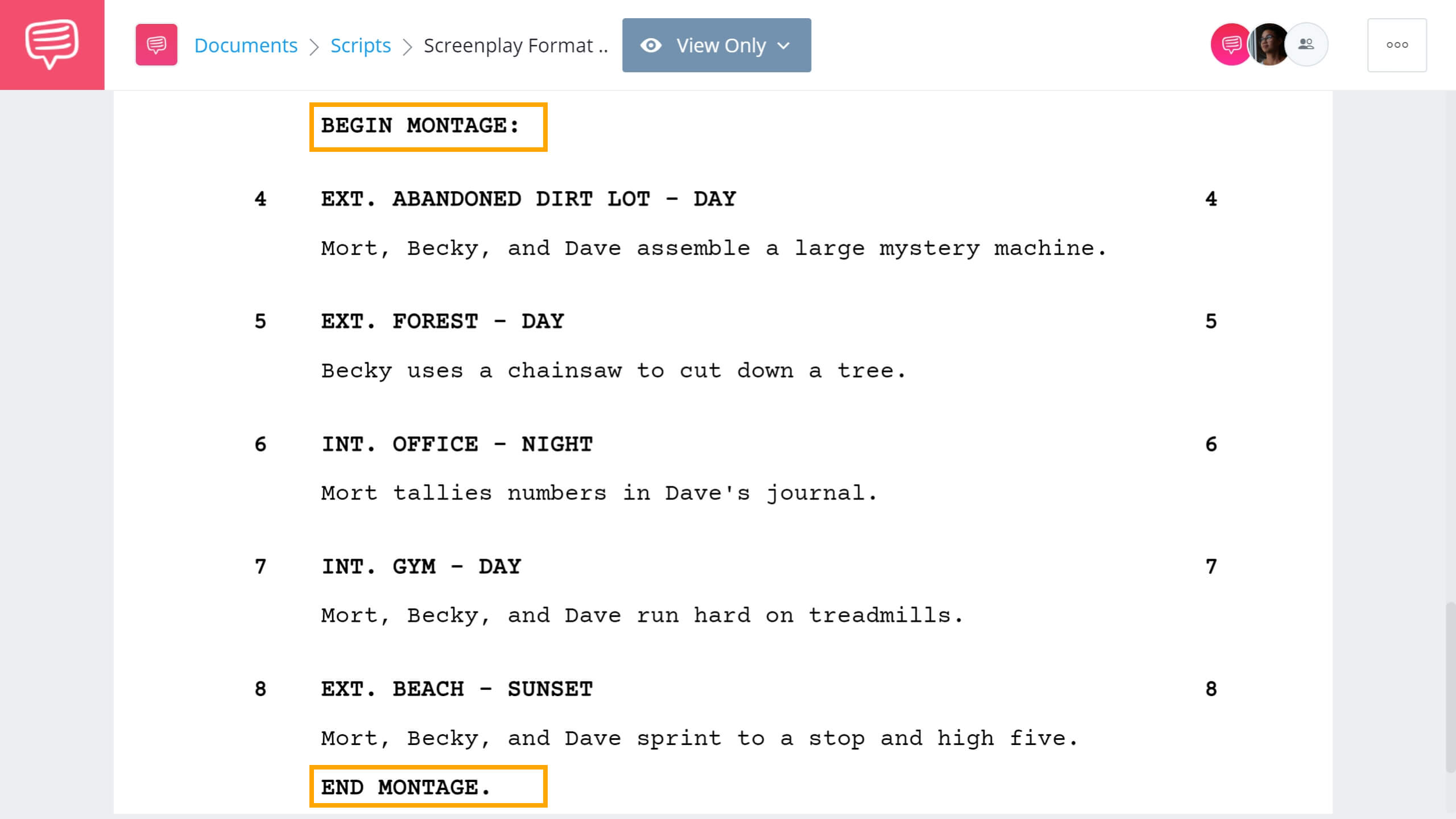

To start a montage, training or otherwise, write “Begin Montage” as if it were a subheader. Then list out your scenes as you normally would.

Once the montage is over and Rocky finally ran up all those steps, close off your montage with “End Montage,” again written as if it were a subheader.

Click below to read a montage example:

There is some leeway when writing a montage. For example, writers often prefer to simply list individual lines, or lines set off by hyphens, within the action to indicate different montage locations and sub-scenes.

Just know that if you want to format your script for production, you'll need a slugline for each individual shot or scene within a montage (as in the montage example above). That's because each location means a different setup and a whole separate set of production concerns.

Lyrics are tricky when it comes to how to format a screenplay, particularly when they have to be matched to action on the screen. No screenwriting software has a “lyrics” element.

An important rule of thumb when learning how to write a screenplay is that, when done properly, one page of film script equals roughly one minute of screen time. Emphasis on roughly.

Since lyrics take up a lot of page space, but don’t take as much time to sing, that can throw the balance off.

You have two options for solving this problem.

You can spread out the lyrics on the page with shots and action directions. This will let you design a little of the choreography and help establish the rhythm and pacing of your big musical number.

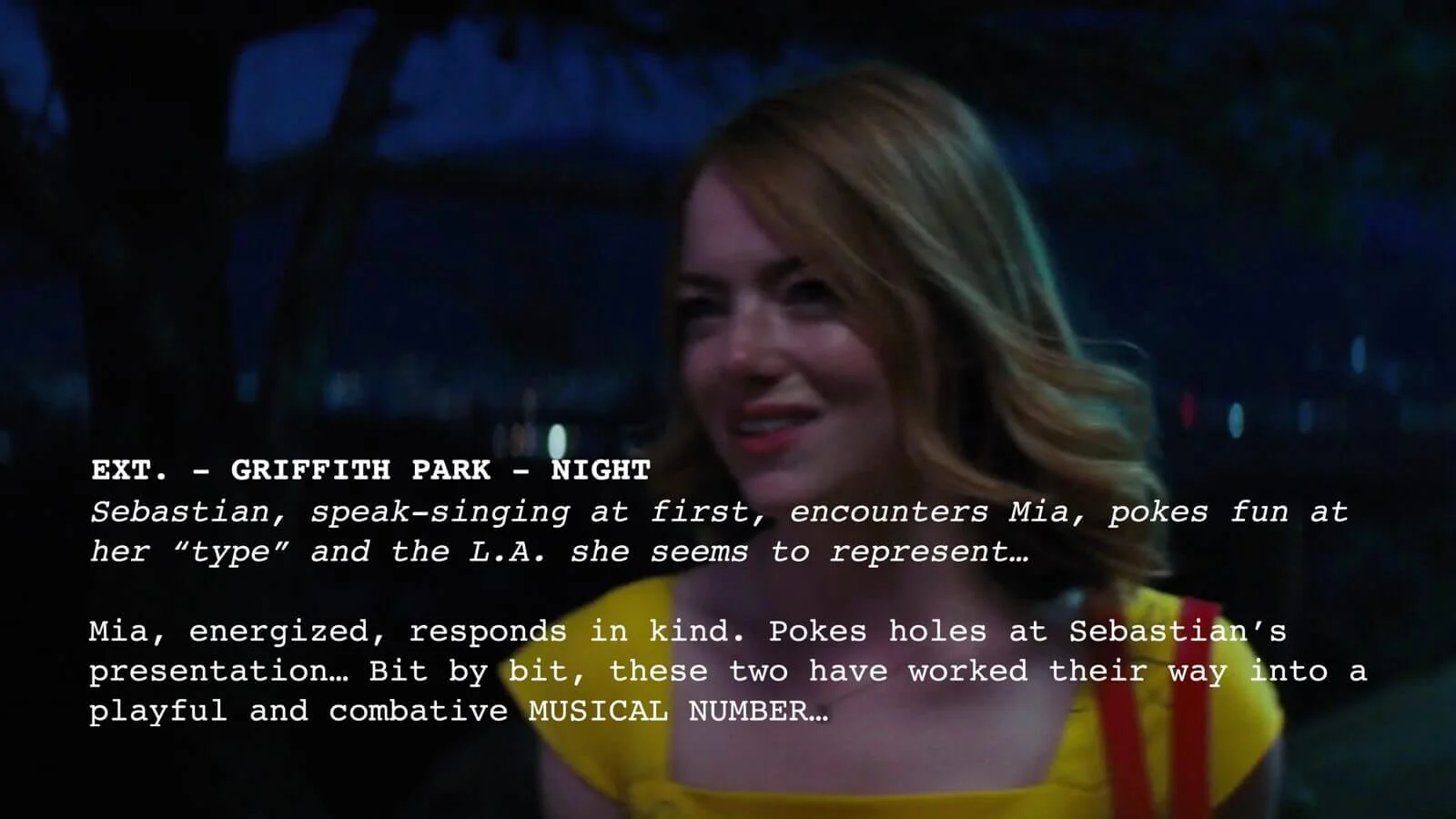

Rather than list out each individual lyric, describe the general feel of the song and the sequence that accompanies it. This is how writer/director Damien Chazelle wrote the musical sequences in his script for La La Land.

While leaving the actual lyrics out of the script, it saves space but just remember to account for the scheduling later. The "musical number" described here might take a lot of time to shoot, more than this simple mention suggests.

Chyrons are the text that appears over the screen — usually used to indicate the time and place of the scene to the audience. You’ll see this sort of thing a lot in military or spy movies.

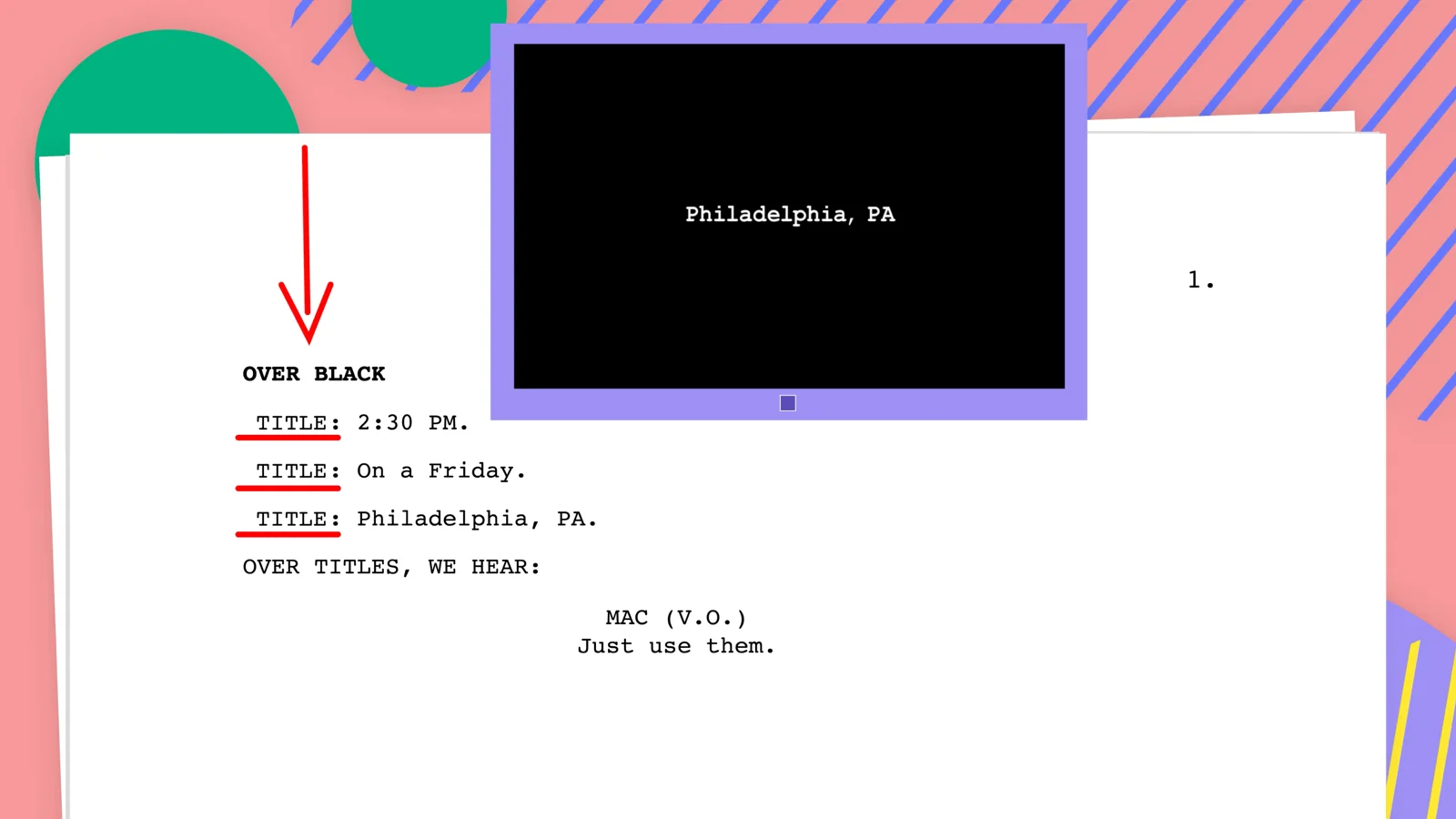

Start an action line with the word “CHYRON” (yes, in all caps) followed by the text of the chyron. Some writers like to use “TITLE” instead of “CHYRON.” It’s a personal choice. If you were using Title, it would look like this:

Other than the scene heading, this is another opportunity to describe the setting of the story or any additional information or context for the reader.

Using "Chyron" would look exactly the same, only swapping the word "Chyron" for "Title." Either one is also considered proper script format.

This is a special kind of formatting that’s only important if you’re writing for network television.

Whenever you reach the end of an act (or teaser) where the show would cut to commercial break, note it by putting “End of Act One,” (or Two or Three) centered and underlined, into your script.

Then you skip a page and put “Act One” (or Act Two or Three) at the very top — again, centered and underlined.

If you’re using screenwriting software, it’s very important that you open your template as a “one hour” or “half hour” drama. If you open it as a feature film script, the screenwriting software may not include that element.

Also, keep in mind that a single-cam sitcom and a multi-cam sitcom have a very different script format.

The single-cam is, essentially, a movie script with act breaks. While the multi-cam has double-spaced dialogued, capitalized action lines, and the new acts begin halfway down the page, and each new scene starts on a new page (as we mentioned).

Make sure you know which one you're writing and then write to that screenplay format. These two types of comedies have quite different tones, aesthetics, and productions. It's critical that the reader, and even more so the production crew, know which one you've written.

It takes practice before screenplay format becomes second nature, even when you’re using a pre-made script template or specialized screenwriting software. Knowing how to format a script comes down to that old adage: "Practice makes perfect." Start writing your script in StudioBinder and we'll handle the formatting for you.