This political cartoon by Thomas Nast depicts Tammany Hall as a tiger attacking democracy.

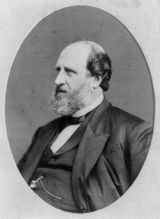

William M. “Boss” Tweed, the most famous leader of Tammany Hall

Corruption at all levels of government characterized the decades following the Civil War. At the national level, corruption ran rampant during the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant (1868-1876). While Grant himself was an honest man, he surrounded himself with men who had considerably less integrity. The term “Grantism” became a synonym for corruption. At the state level, governments struggled to deal with widespread corruption during and after the Reconstruction years. At the local level, urban political machines—headed by political bosses—established dominance over city politics.

The fast and expansive urbanization that took place after the Civil War brought a myriad problems to America’s cities. City governments were simply not prepared to deal with the type of issues they faced. The task of running the nation’s largest cities fell to the only entities that seemed capable of handling it: political machines.

Political machines, political organizations led by party “bosses,” became entwined in all aspects of municipal government. Party bosses gave jobs to their supporters, and they mastered a system of kickbacks, with contractors or businesses paying politicians in order to get government contracts. This resulted in services being performed for the cities, such as streets being paved, but at exorbitant prices to taxpayers. Machines also helped new immigrants with basic needs, including food and shelter, in return for loyalty. The best known urban political machine was New York City’s Democratic Tammany Hall.

In spite of their tremendous power, political machines did not prove successful in the long run because they concerned themselves only with power and immediate successes and did not address or solve long-term urban problems, such as working conditions. They were “successful” in the short term—meeting immediate needs and winning elections—but not in dealing with long-term issues.

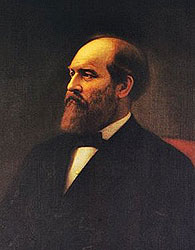

James A. Garfield

While rapid industrialization and urbanization helped some Americans immensely, it created problems for others. How did politicians and government respond to these issues during the Gilded Age? The prevailing philosophy was laissez faire, in which the government left the economy and its problems alone and did not intervene.

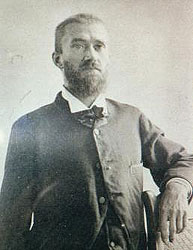

Charles J. Guiteau

American leadership during the Gilded Age did not come from the White House. The era’s presidents were not strong leaders. Grover Cleveland, who ran for the presidency on a reputation of honesty and efficiency, represented the best semblance of leadership during the period. If the presidents were not leading the nation, who was? The city’s political machines, and the nation’s legislature.

Congress, which had assumed a great deal of power during Reconstruction, maintained power into the Gilded Age. But the legislature operated under the spoils system—officeholders put their party members or friends into office. By the 1870s it seemed as if the “spoils” were the main motivation for winning office. The spoils system came to a head, and discredited itself, when President James A. Garfield was assassinated in 1881. Garfield’s assassin, Charles J. Guiteau, claimed that he shot the president because he and his friends had been denied government jobs. In 1883, Congress passed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, one of the few important pieces of legislation passed during this period. The act mandated that government jobs be filled on the basis of merit rather than politics.

As a whole, politicians of both parties ignored the major issues of the day. Both Republicans and Democrats preached a laissez faire philosophy of government. This approach tended to help the robber barons and hurt the average American. Farmers became the first group of Americans to protest the laissez faire approach. Play the Gilded Age Presidents interactive to learn the names, party affiliations, and years served for this period’s leaders.